|

During the years that the Madras Bulwark was being constructed (MM, August 1st) the English had begun moving out of the Fort and the need arose for a church close to the Great Choultry Plain. Bishop Middleton, Bishop of India, Burma and Ceylon, had thundered from Calcutta about the ugliness of buildings being erected as churches and so there was pressure to create something classical. Designed by Chief Engineer Col. James Caldwell and supervised by Major de Havilland, St George’s Cathedral was completed in 1816, the consecration being done by a much-pleased Middleton. de Havilland’s reputation was made. No doubt, in order to be close to this great project, he purchased land in Poodoopauk (present day Pudupet abutting Mount Road) and built his residence. This was an unusual construction for it comprised what was later described by Love as two castellated circular towers, standing on the opposite ends of a vast garden. These became the Eastern and Western Castlets. The intervening garden would be put to good use by de Havilland when he was entrusted with his next project – the building of St Andrew’s Kirk in 1816. de Havilland decided that the new structure would be circular in plan and topped with a dome.

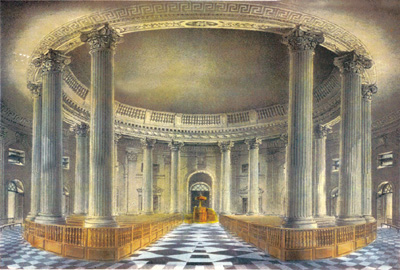

View of the magnificent interior of St. Andrew's Church, Madras, built by de Havilland. (Colour lithograph by

J.B. Maxwell after Gantz, 1825.)

|

In order to closely study the native technique of dome building, he had a team build a dome in the garden of his house, just as the arch had been built in Mysore. Having observed them closely, he gained confidence and went ahead with the construction of the kirk. The story of the foundations of the kirk needing terracotta wells to support them (again a native technique that de Havilland borrowed) is too well-known to merit repetition. The kirk when completed was (and is) magnificent but the dome resulted in poor acoustics. When questioned about this de Havilland blamed it all on the “voice of the reverend!” He went on to write An Account of St Andrews Church in 1821, which later was included in a more detailed paper by him – Delineations and Descriptions of Public Edifices in and near Madras (1826).

According to the Rev A. Westcott (Our Oldest Indian Mission, A Brief History of the Vepery (Madras) Mission, Madras Diocesan Press, 1897), de Havilland was asked to take a look at the possibility of restoring St. Mathias’ Church in Vepery. He reported it to be beyond repair and bids were invited for a new building. The quote of John Law, a graduate of the Male Orphan Asylum, was the lowest. Work began and de Havilland, greatly offended at losing the bid, waited till the church was completed in 1825, complete with a magnificent steeple. Then, in his capacity as Chief Engineer of the Presidency, he inspected the building and declared that the steeple was a security risk, for guns could be trained on the Fort from its pinnacle! Fully aware that the kirk’s steeple was just as high he declared that, unlike the St. Mathias steeple, the former “yielded no facility for the mounting of mortars and howitzers.” His word was taken and the St. Mathias steeple was demolished at great expense and replaced with a diminutive tower which, according to Westcott, was a lasting testimony to de Havilland’s spite.

This colourful character appears to have retired to his native Guernsey in 1825. His father had died in 1821 and it was necessary for him to return and manage the estates. Among his last acts was to compile a comprehensive report on what he felt was wrong with the Madras Corps of Engineers. Dated November 23, 1821, it also had suggestions for improving the quality of engineers and what enhancements in skill was needed for them to take up civil works. This led to fiery exchanges between him and Col. R.B. Otto, the then Quarter Master General of the Madras Army. Ultimately, however, de Havilland’s suggestions were acted upon. In Guernsey, he built/rebuilt (sources differ on this) Havilland Hall in the classical style. He entered public life and was elected Justice of the Royal Court. He died at the age of 90 in 1866. He clearly did not lose touch with Madras for, in 1836, he warmly supported Col. Arthur Cotton in his scheme for building a breakwater off Madras, the first of the many projects that ultimately culminated in the Madras Harbour in the early 1900s.

What of de Havilland’s residence in Madras? It is very likely that he sold his property before he left in 1825, though it is unclear as to who purchased it from him. By 1887, when Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee was celebrated, Eastern Castlet was home to Addison’s Press. In his Narrative of the Celebrations of the Golden Jubilee of Queen Victoria in the Presidency of Madras, Charles Lawson (Madras, 1887) mentions that Addison’s had placed a large flag on the Eastern Castlet. It would appear that this castlet was subsequently demolished when Addison’s got into the retailing of cars and built their handsome showroom on Mount Road. Today, that showroom is one of the offices of Amalgamations Limited, which acquired Addison’s in the 1940s.

Western Castlet appears to have survived much longer, though its exact location is even more difficult to identify. Considering that most accounts say it was off Mount Road, it is very likely that Eastern Castlet was on Mount Road itself and Western Castlet to its rear. After they were divided, it is probable, Western Castlet was accessed by a service lane from Mount Road.

Western Castlet became Western Castle in the 1920s. At around this time, Lady Willingdon (then First Lady of Madras) founded the South Indian Nursing Association whose members were trained Anglo-Indian and European nurses, almost all of them working at the Lady Willingdon Nursing Home. The nursing home functioned from 1931 at Western Castle and remained there till it shifted in 1951 to Pycroft’s Garden Road. In the 1990s, this facility became a branch of the Sankara Nethralaya. The Nursing Association merged with the Lady Ampthill Nurses Institute (founded in 1904) in 1998 and formed the nucleus of the Chennai Willingdon Corporate Foundation, focussing on public service programmes.

But what happened to Western Castlet/Castle is a mystery. Was it demolished? What is even more intriguing is that not a single photograph of either castlet has survived. There is, however, an early aquatint in the British Library that shows how the two structures looked in de Havilland’s time. Love was clearly not entirely accurate when he described them as two circular towers. Each comprised a central tower with three or four smaller circular towers surrounding the central tower and sharing common walls with it. By the time of the British Library aquatint, a compound wall had come up between the two castlets, thereby indicating that the property had been divided into two. Another garden house can be seen in the distance, but without knowing the coordinates from which the painting has been executed it is difficult to identify as to which building is that. And so the exact location of the two castlets remains a mystery.

But if the space that answers to the description of where Eastern Castlet stood is indeed the present Addison showroom, then certain possibilities emerge. As you walk to the rear, down the lane running beside Addison, and which is rather grandiosely referred to as TNEB Avenue, you come to a vast compound that now houses the Electricity Board offices. Old-timers recall an old bungalow with a pedimented portico supported by columns standing here, which was demolished to make way for the TNEB’s ghastly creations. Was this where the Lady Willingdon Nursing Home was housed? If so, this garden house must have been a successor to Western Castlet, for its description in no way matches what is shown in the British Library picture. The name of the older building must have been carried forward and applied to the later structure as well.

What is interesting is that this lane still houses a couple of heritage buildings. There is the TNEB Club, which must clearly be at least 100 years old. And adjacent to this, in a separate compound, stands an old bungalow now occupied by a senior army officer. But were they also once part of de Havilland’s property? If only stones could speak.

|